1991: Part 2, Value Propositions

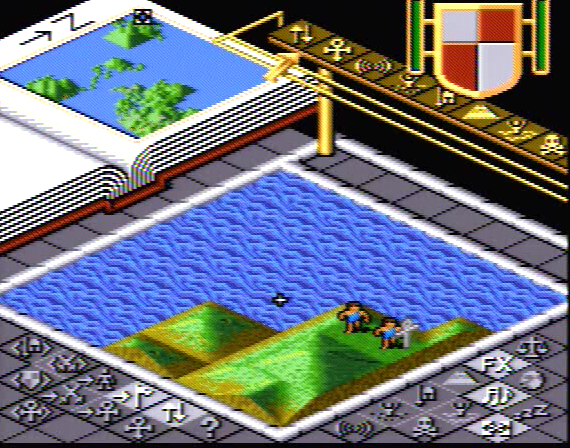

Gamepro referred to the SNES library as "fully three-quarters ... upgrades from 8-bit programs," even while it referred to Super Ghouls N Ghosts as a "new generation." 1 Previews of the SNES library over the next five pages were oddly broken up by advertisements, the first two of which featured Genesis games prominently along with their prices. Over thirty five SNES games were previewed in typical promotional fashion however and almost all of them are made by third parties that owners of Nintendo's first console recognized.

Gamepro referred to the SNES library as "fully three-quarters ... upgrades from 8-bit programs," even while it referred to Super Ghouls N Ghosts as a "new generation." 1 Previews of the SNES library over the next five pages were oddly broken up by advertisements, the first two of which featured Genesis games prominently along with their prices. Over thirty five SNES games were previewed in typical promotional fashion however and almost all of them are made by third parties that owners of Nintendo's first console recognized.

Never to be upstaged, EGM dedicated twelve pages to the SNES Buyer's Guide within their August 1991 issue, which posted review scores for sixteen games and previews for thirty four more. EGM's review system had four separate reviewers rank a game on a scale of one to ten. The SNES buyer's guide ranked three games with nines and eights, five games scored eights and sevens, and eight more were scored four through six. That is, half of the SNES games reviewable at launch came recommended by EGM's reviewers, and half were relegated to mediocre or worse.2

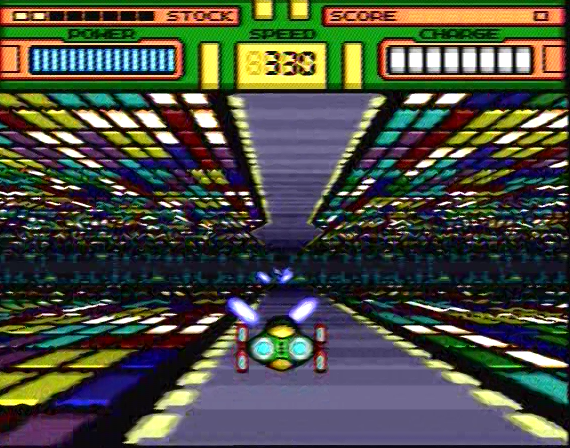

In addition to amassing a large game library for the Genesis, Sega had debuted two things that summer which stole these magazine's spotlights from Nintendo. Sonic the Hedgehog and the Mega CD-ROM add-on combined with one hundred and fifty nine other Genesis games were impossible for game magazines, and by reflection consumers, to ignore.3 Sega's CD add-on for the Genesis will be dealt with in more detail in its own section, but its show floor debut in summer of 1991, months from its Japanese release, lent Sega significant media coverage. Sega also managed to spend more on advertising than ever before, as EGM's October issue contained a 96 page promotion for everything that was licensed for release on the Genesis.4

In addition to amassing a large game library for the Genesis, Sega had debuted two things that summer which stole these magazine's spotlights from Nintendo. Sonic the Hedgehog and the Mega CD-ROM add-on combined with one hundred and fifty nine other Genesis games were impossible for game magazines, and by reflection consumers, to ignore.3 Sega's CD add-on for the Genesis will be dealt with in more detail in its own section, but its show floor debut in summer of 1991, months from its Japanese release, lent Sega significant media coverage. Sega also managed to spend more on advertising than ever before, as EGM's October issue contained a 96 page promotion for everything that was licensed for release on the Genesis.4

During the Christmas season of 1991 EGM and Gamepro printed reader letters and 16-bit buyer's guides  that defined the game industry as a three way race with Sega and Nintendo roughly equal in all respects. Reader letters showed a disparity rarely seen in the US game industry over which system carried absolute superiority. One William Miller of Lawndale California simplistically compared popular Genesis and SNES games, the two system's central processors, and included the Sega CD to conclude "the S-NES is totally lame." Meanwhile Brian McSwain of Sanford Florida felt that the Sega CD would merely bring the Genesis to equality with the SNES' "graphics, sound, play control and Mode 7." John Sikes of Detroit Lakes Minnesota assumed that most of the advantages that the Sega CD would provide were already offered by the TurboGrafx-16 CD-ROM attachment. EGM itself responded to Ron Ward of Newark California to point out that the Sega CD would have more RAM than the Turbo CD and would be more proficient at scaling and rotation than the SNES' Mode 7. Noah Freer of Los Angeles just wrote in to compliment Sega's 96 page advertisement in EGM's October issue.5

that defined the game industry as a three way race with Sega and Nintendo roughly equal in all respects. Reader letters showed a disparity rarely seen in the US game industry over which system carried absolute superiority. One William Miller of Lawndale California simplistically compared popular Genesis and SNES games, the two system's central processors, and included the Sega CD to conclude "the S-NES is totally lame." Meanwhile Brian McSwain of Sanford Florida felt that the Sega CD would merely bring the Genesis to equality with the SNES' "graphics, sound, play control and Mode 7." John Sikes of Detroit Lakes Minnesota assumed that most of the advantages that the Sega CD would provide were already offered by the TurboGrafx-16 CD-ROM attachment. EGM itself responded to Ron Ward of Newark California to point out that the Sega CD would have more RAM than the Turbo CD and would be more proficient at scaling and rotation than the SNES' Mode 7. Noah Freer of Los Angeles just wrote in to compliment Sega's 96 page advertisement in EGM's October issue.5

Despite the incongruity of comments EGM held nothing back in favor of the Super Nintendo. In EGM promotion speak the SNES was "unlike any other consumer game system," and it captured "the crisp color and detailed graphics that today's players are demanding." The magazine also listed the system's advantages as scaling, rotation and audio and its disadvantages as slowdown, flicker, and limited objects on screen.6 That objects on screen observation is particularly important, as the Super NES is supposed to have the strongest "sprite engine" of the three 16-bit consoles by a wide margin. Whether the cause be its slower CPU or poor programming, SNES games always struggle to put as many characters and objects on screen as top TG16 games. Genesis games handily beat both the TG16 and SNES libraries in the category of sprites on screen. In order for the SNES to live up to its prelaunch hype as a "16-bit Mega Monster" and the "Ultimate in 16-bit gaming" these deficiencies needed to be ironed out.

Despite the incongruity of comments EGM held nothing back in favor of the Super Nintendo. In EGM promotion speak the SNES was "unlike any other consumer game system," and it captured "the crisp color and detailed graphics that today's players are demanding." The magazine also listed the system's advantages as scaling, rotation and audio and its disadvantages as slowdown, flicker, and limited objects on screen.6 That objects on screen observation is particularly important, as the Super NES is supposed to have the strongest "sprite engine" of the three 16-bit consoles by a wide margin. Whether the cause be its slower CPU or poor programming, SNES games always struggle to put as many characters and objects on screen as top TG16 games. Genesis games handily beat both the TG16 and SNES libraries in the category of sprites on screen. In order for the SNES to live up to its prelaunch hype as a "16-bit Mega Monster" and the "Ultimate in 16-bit gaming" these deficiencies needed to be ironed out.

Instead of listing hardware specifications and eyeballing graphical glitches Gamepro listed the prices, described the game libraries and controllers, and forecasted what each system's library would be like in 1992. The Genesis was listed at $149 with Sonic The Hedgehog and one control pad, another controller brought the total cost to "only $30 less than a Super Nes." Sega's game library was described as "a terrific mix of licensed character games...sports simulations...arcade action carts...and Weird Funko-Dudes Lost in Outer Space." Game costs were $45-$60 although "8-megabit role playing games" were $75. Special note was given to the Power Base Converter, listed at $35, which allowed "backward compatibility with dozens of great 8-bit Master System titles." Wrapping up, Gamepro assured its readers that the next year would provide even more of the same qualities to the Genesis library, and numbered the total release list at one hundred and fifty nine.7

Instead of listing hardware specifications and eyeballing graphical glitches Gamepro listed the prices, described the game libraries and controllers, and forecasted what each system's library would be like in 1992. The Genesis was listed at $149 with Sonic The Hedgehog and one control pad, another controller brought the total cost to "only $30 less than a Super Nes." Sega's game library was described as "a terrific mix of licensed character games...sports simulations...arcade action carts...and Weird Funko-Dudes Lost in Outer Space." Game costs were $45-$60 although "8-megabit role playing games" were $75. Special note was given to the Power Base Converter, listed at $35, which allowed "backward compatibility with dozens of great 8-bit Master System titles." Wrapping up, Gamepro assured its readers that the next year would provide even more of the same qualities to the Genesis library, and numbered the total release list at one hundred and fifty nine.7

NEC's console was by contrast introduced with a zinger about its 8-bit CPU making it "less advanced" than the Genesis or SNES. The Turbo CD attachment was brought up only to mention that it was not selling well and that Sega and Nintendo would likely release something similar. The TurboGrafx retail package cost $99 with one controller and Keith Courage in Alpha Zones. To which Gamepro complained about why Keith Courage, released in 1989, had not been replaced with the $50 "Mario equivalent" Bonk's Adventure. Also of note is that the TurboGrafx required an expensive peripheral called the Turbo Booster or Turbo Booster Plus, $35 or $60 respectively, to hook up with newer televisions using Composite A/V cables. In addition, to play multiplayer games on the TG16 one had to purchase an extra controller at $20 and a TurboTap 5-Player Adapter at $20.8 Assuming that Gamepro was correct to compare the value proposition of each system, the Turbo Booster, TurboTap and an extra controller alone brought the total starting cost to the same as a Genesis with an extra gamepad. Adding any game from 1991 to the mix sent the total cost of the "entry level" TG16 over $200.9 Gamepro proceeded to trash the TG16's library as limited and quirky to US audiences, before explaining that it had "bottomed out" for players without the CD add-on. The Turbo CD itself was priced at $299 and its games cost between $19 and $62. The total library for the TurboGrafx-16 and the Turbo CD at the end of 1991 was reported to be sixty-seven "regular games" and fourteen CD games.10

NEC's console was by contrast introduced with a zinger about its 8-bit CPU making it "less advanced" than the Genesis or SNES. The Turbo CD attachment was brought up only to mention that it was not selling well and that Sega and Nintendo would likely release something similar. The TurboGrafx retail package cost $99 with one controller and Keith Courage in Alpha Zones. To which Gamepro complained about why Keith Courage, released in 1989, had not been replaced with the $50 "Mario equivalent" Bonk's Adventure. Also of note is that the TurboGrafx required an expensive peripheral called the Turbo Booster or Turbo Booster Plus, $35 or $60 respectively, to hook up with newer televisions using Composite A/V cables. In addition, to play multiplayer games on the TG16 one had to purchase an extra controller at $20 and a TurboTap 5-Player Adapter at $20.8 Assuming that Gamepro was correct to compare the value proposition of each system, the Turbo Booster, TurboTap and an extra controller alone brought the total starting cost to the same as a Genesis with an extra gamepad. Adding any game from 1991 to the mix sent the total cost of the "entry level" TG16 over $200.9 Gamepro proceeded to trash the TG16's library as limited and quirky to US audiences, before explaining that it had "bottomed out" for players without the CD add-on. The Turbo CD itself was priced at $299 and its games cost between $19 and $62. The total library for the TurboGrafx-16 and the Turbo CD at the end of 1991 was reported to be sixty-seven "regular games" and fourteen CD games.10

The Super Nintendo segment placed it at the "top-of-the-line price of $199.95," which included Super Mario World and two controllers. The Genesis and TG16 controllers were described in the previous sections, with the Genesis pad having a total of three "fire buttons" a start button and a directional pad and the TG16 pad being "the same as the NES." The SNES pad was conversely called "the most advanced anywhere" and potentially "too complex" for children. Nintendo's 16-bit library was presented as updates to NES games, with the cons being disappointing sequels and no NES compatibility. Gamepro's final analysis boiled down to "price, games, hardware power, and future expansion." The TurboGrafx was relegated to the "low end" inexpensive entry system with "psuedo 16-bit" shooters and multiplayer games. The TG16 was clearly excluded from Gamepro's consideration, which consumers had apparently already done, so the value proposition left only Nintendo and Sega products. The Genesis and SNES were portrayed as roughly equal in hardware capabilities, with the SNES' Mode 7, higher colors and "stronger sprite engine" being offset by being "only half the speed of the Genesis." In terms of library the Genesis was unequivocally found to have won by a landslide in 1991.11

The Super Nintendo segment placed it at the "top-of-the-line price of $199.95," which included Super Mario World and two controllers. The Genesis and TG16 controllers were described in the previous sections, with the Genesis pad having a total of three "fire buttons" a start button and a directional pad and the TG16 pad being "the same as the NES." The SNES pad was conversely called "the most advanced anywhere" and potentially "too complex" for children. Nintendo's 16-bit library was presented as updates to NES games, with the cons being disappointing sequels and no NES compatibility. Gamepro's final analysis boiled down to "price, games, hardware power, and future expansion." The TurboGrafx was relegated to the "low end" inexpensive entry system with "psuedo 16-bit" shooters and multiplayer games. The TG16 was clearly excluded from Gamepro's consideration, which consumers had apparently already done, so the value proposition left only Nintendo and Sega products. The Genesis and SNES were portrayed as roughly equal in hardware capabilities, with the SNES' Mode 7, higher colors and "stronger sprite engine" being offset by being "only half the speed of the Genesis." In terms of library the Genesis was unequivocally found to have won by a landslide in 1991.11

Much more prone to hyperbole, EGM asserted that "1991 saw the first real explosion of 16-bit interest, spurred largely by Nintendo and the long-awaited release of their Super Nintendo Entertainment System." Editor Ed Semrad also mentioned that price drops by both NEC and Sega and slowing NES game sales were defining characteristics of the year.12 Reducing thousands of letters each month to a few pages, EGM spent two columns of its December letter section over when the newly released Street Fighter 2 arcade game would be brought home to the Super NES.13 Street Fighter 2 is thought to have been responsible for revitalizing the arcade industry in the US, so its exclusive release on the SNES would have been very significant. Yet the battle for 16-bit supremacy was no longer one sided. D.J. Thomas of Houston Texas wrote EGM to ask which system and games won awards that year. EGM responded that it had released an entirely separate issue for the purpose of its annual awards stating "as to who won the best game of the year, and the best system of the year ... they're either Nintendo or Sega products."14

Much more prone to hyperbole, EGM asserted that "1991 saw the first real explosion of 16-bit interest, spurred largely by Nintendo and the long-awaited release of their Super Nintendo Entertainment System." Editor Ed Semrad also mentioned that price drops by both NEC and Sega and slowing NES game sales were defining characteristics of the year.12 Reducing thousands of letters each month to a few pages, EGM spent two columns of its December letter section over when the newly released Street Fighter 2 arcade game would be brought home to the Super NES.13 Street Fighter 2 is thought to have been responsible for revitalizing the arcade industry in the US, so its exclusive release on the SNES would have been very significant. Yet the battle for 16-bit supremacy was no longer one sided. D.J. Thomas of Houston Texas wrote EGM to ask which system and games won awards that year. EGM responded that it had released an entirely separate issue for the purpose of its annual awards stating "as to who won the best game of the year, and the best system of the year ... they're either Nintendo or Sega products."14

The SNES' primary weakness came up again as Doug Erickson of Chehalis Washington mused to EGM about why Nintendo went with a "slow processor" instead of a "80386 or 68000 series processor." Ignoring the ignorance over which x86 series processor was equivalent to the Genesis' CPU, Erickson's question is substantial for several reasons. Erickson's letter shows that EGM's readers had been bombarded by technical specifications enough to actually start questioning the engineering of a proprietary device as though they were qualified to do so. His assertion also shows that consumers in 1991 were comparing games across platforms and manufacturers. Nobody would have felt that the SNES was slow if they only compared it to Nintendo's NES. That is in contrast to what will happen in future generations where entire markets migrate to a new console without shopping other manufacturers' products. EGM revealed that "a lot of letters" like Erickson's were questioning Nintendo's engineering "wisdom," eliminating the likelihood that this letter was not representative of a typical consumer. The Japanese market's preference for slower moving Role Playing Games and that game developers would learn to better exploit the SNES' hardware were offered by EGM as alternative views to Erickson's and others.15 It should not be ignored, though, that this kind of exchange of generally negative comments would not have happened if Nintendo and its game advertising was still the dominant force in the industry.

The SNES' primary weakness came up again as Doug Erickson of Chehalis Washington mused to EGM about why Nintendo went with a "slow processor" instead of a "80386 or 68000 series processor." Ignoring the ignorance over which x86 series processor was equivalent to the Genesis' CPU, Erickson's question is substantial for several reasons. Erickson's letter shows that EGM's readers had been bombarded by technical specifications enough to actually start questioning the engineering of a proprietary device as though they were qualified to do so. His assertion also shows that consumers in 1991 were comparing games across platforms and manufacturers. Nobody would have felt that the SNES was slow if they only compared it to Nintendo's NES. That is in contrast to what will happen in future generations where entire markets migrate to a new console without shopping other manufacturers' products. EGM revealed that "a lot of letters" like Erickson's were questioning Nintendo's engineering "wisdom," eliminating the likelihood that this letter was not representative of a typical consumer. The Japanese market's preference for slower moving Role Playing Games and that game developers would learn to better exploit the SNES' hardware were offered by EGM as alternative views to Erickson's and others.15 It should not be ignored, though, that this kind of exchange of generally negative comments would not have happened if Nintendo and its game advertising was still the dominant force in the industry.

- 1. "Pizza X," "Super NES Made In Japan, The Raw and the Cooked: Pizza X at the Famicom Space World Show," Gamepro, August 1991, 26-27.

- 2. "Super NES Video Game Buyer's Guide," Electronic Gaming Monthly, August 1991, 59-72.

- 3. "Slasher Quan," "So You Want to Buy a 16-Bit System...," Gamepro, December 1991, 48.

- 4. Electronic Gaming Monthly, October 1991, 4.

- 5. "Interface: Letters to the editor, The Great Debate:..Super-NES vs Genesis vs Turbo," Electronic Gaming Monthly, 14.

- 6. "Super Nes Buyer's Guide, Insert Coin, Super 16-Bit Hardware! Super Charged Games! Super Nintendo!," Electronic Gaming Monthly, November 1991, 160.

- 7. "Slasher Quan," "So You Want to Buy a 16-Bit System...," Gamepro, December 1991, 48.

- 8. "Totally Turbo: The Total Source for TurboGrafx-16," Electronic Gaming Monthly, August 1991, 91.

- 9. "Slasher Quan," "So You Want to Buy a 16-Bit System...," Gamepro, December 1991, 49.

- 10. "Slasher Quan," "So You Want to Buy a 16-Bit System...," Gamepro, December 1991, 50.

- 11. "Slasher Quan," "So You Want to Buy a 16-Bit System...," Gamepro, December 1991, 50.

- 12. Ed Semrad, "insert coin: The EGM Difference," Electronic Gaming Monthly, December 1991, 8.

- 13. "Interface: Letters To The Editor, Street Fighter 2 for S-NES," Electronic Gaming Monthly, December 1991, 10.

- 14. "Interface: Letters To The Editor, 1992 Awards???," Electronic Gaming Monthly, December 1991, 12.

- 15. "Interface: Letters To The Editor, Slow S-NES," Electronic Gaming Monthly, December 1991, 12.

- Printer-friendly version

- 29641 reads