Reviews

Game Pilgrimage reviews will be focused on documenting facts, whether they be about games or other published materials. The goal will be to catalog facts about games and game systems from primary sources. As a rule, any unsupported personal opinion will be flagged as such, and any first hand account will be put in context with the recollections of other eye witnesses.

Advertising

Here be reviews of various advertising campaigns, emphasizing fact checks and corrections.Nintendo

Reviews of Nintendo's Advertising.SMASHING The Myth About Speed and Power

SMASHING: The Myth of Speed and Power was a Nintendo print advertising campaign in 1994 against Sega's Blast Processing Television commercials. The advertisement was designed to look like a regular magazine article, and focused heavily on the Genesis not having any kind of special chip called the "blast processor" or a special chip that produces "blast processing." Nintendo elevated its custom processors and Dynamic Memory Access (DMA) design, above what was already found in the Sega Genesis, while pointing out other marginally advantageous, misleading, or vague to meaningless hardware specifications. SMASHING is simply a case of ill-phrased self promotion.

As the Blast processing TV commercial clearly shows, Sega only stated the Genesis "has blast processing." Sega even admitted to the press that Blast Processing was just a marketing buzz word. Endless discussion ensued about whether Blast Processing emphasized the Genesis CPU's speed over the Super Nintendo's, DMA, or some software technique for moving objects faster than the screen would scroll.1 Debate over each technical aspect of that argument will be covered more thoroughly in a review of the Blast Processing advertising campaign, Nothing from Sega ever claimed there was a special chip in the Genesis that was called or produced "blast processing". Interestingly, it was Nintendo that created the notion of a Blast Processor and the game media ran with it.

The average consumer would have seen the actual Blast Processing commercial (4.4 MB) by the time of seeing this fake editorial:2

Column one, titled "A Blast of Hot Air," also includes Nintendo's first fallacy that the SNES could handle Sonic or any game character while scaling him "so large that you'd see each individual hedgehog hair (not a pretty sight) and ... rotate his background until he really turned blue." The Super Nintendo could not scale sprites. In the SNES' seventh background mode, it could only scale a single 256 color background. Within said mode, no object would enhance in detail as it approached the screen. Any object or background, when zoomed in, would only show the pixels that were always there until all that was visible was a few different colored squares. The reader may decide whether or not that was a pretty sight, but no SNES game would ever show enhanced detail for any background as it scaled into the screen. Column two and three begin Nintendo's real thrust with this advertisement, poorly fact checked promotion of customized processors.

Notably omitted under "True Power Processing" was an admission that Nintendo waited too long or failed to deliver on its promises with the Super Nintendo. The gaming media in early 1992 showed Nintendo only slightly less in favor than usual.3 After the release of Street Fighter II on SNES in late 1992 critique of anything on a Nintendo platform was hard to find. This 1994 article returned to Nintendo's pre-launch hype by emphasizing the Super Nintendo's "six customized chips," DMA, and of course Mode 7, over Sega's "mainly off-the-shelf parts."

As proof, Nintendo claimed to have revolutionized sports games without any specific examples. Column two similarly runs into factual errors. Comparing 32,000 colors for the SNES to 256 for the Genesis, with 256 colors on screen simultaneously to only 64, Nintendo's advertisement stumbles first in its most obvious way. The Genesis actually has a 512 color (9-bit) master palette to choose from, and the Super Nintendo could only actually display 256 colors in the single background Mode 7.4 Similarly, Nintendo compares the SNES' total on screen sprite limitation of 128 to the Genesis' 80 while failing to mention the sprite size limitations. No admission or explanation is made here as to why SNES games usually had fewer objects on screen than similar Genesis titles.

One reason as to why is Sega's Genesis has a more flexible sprite size limitation. Any object from 8x8 to 32x32, in increments of 8 pixels wide or tall, can be displayed on screen simultaneously. Conversely Nintendo limited the SNES by only allowing one of two sizes on screen at once, such as 16x16 and 32x32.5 Due to this and other more technical factors, actual games were more likely to fill up the screen with the Genesis' sprite table than with the SNES' limitations.

"Superior NES" continues Nintendo's self promotion by means of a bullet list attempting to show how much "more" the SNES has than the Genesis. Listed here are two Picture Processing Units (PPUs), which are actually just one chip with two processors on one die that would not function without one another, as opposed to the Genesis' single VDP. Nintendo also claims "6 custom designed chips for video games as opposed to only 2" are necessary for more effects, colors and "better sound". Also included but not explained are "almost twice the internal memory" and a very obscure claim of "data retrieval" supposedly being "88% faster than Genesis." Without considering other factors, like the SNES' limited bandwidth and its choice for planar graphics, it's hard to understand why, even with more memory and supposed faster "data retrieval", SNES games like Mickey Mania, Mr.Nutz, Out Of This World, Phantom 2040 have noticeable loading times when compared to their Genesis versions.

SNES's signal to noise ratio was also inexplicably "2.5 times better." Wrapping up, Nintendo felt the need to point out twelve buttons on the controller to eight on the Genesis 6-button pad, which strangely counts each direction on the directional pad as a button. Jumping to the bottom of the first column, Nintendo selected screenshots of Alien 3, The Lost Vikings and Nigel Mansell's World Championship Racing to exemplify the SNES' graphics fidelity over that of the Genesis. Not one of these games would go on to be considered typical examples of art inspired Genesis titles.

Nintendo's second to last column, titled "For The Super NES Only," begins by claiming Sonic the Hedgehog 2 is only worth one fast play through. Somehow the SNES also exclusively provides game designers "more meat to sink their teeth into." Thirty four SNES titles are then rattled off that somehow could never be replicated on the Genesis. Finally, "Get Real, Get Nintendo" claims that the Genesis simply does not have the best games. Once again Nintendo digressed here by listing off more games and game developers, some of which were exclusive to Nintendo and some that were also on Genesis.

The final column concluded Nintendo's fake editorial with another list of mostly irrelevant facts. Titled "Q&A: The Questions That Count," these irrelevant questions only cede to Sega the color of the console being black and its mascot being a "European porcupine." The rest of the list, like the fake editorial in its entirety, over emphasized and simplified the number of special chips in the SNES.

Only speculation can answer why game magazines of the day, which unabashedly claimed to be free advertising for the biggest publishers,6 failed to print this fake article as one their own. To the present day one will occasionally see game magazine editors or gamers online say that Sega lied about blast processing, or that Sega claimed that there was a special chip within the Genesis. The source for that emotional opinion is right here in Nintendo's own 1994 anti-Sega advertising campaign.

- 1. "sheath", "Sega Genesis vs Super Nintendo," (November 8, 2009, accessed August 12, 2013) available from http://www.gamepilgrimage.com.

- 2. Thanks to http://www.majkel.mds.pl/html/reklama/indexENG.html

- 3. "sheath," "1991, Hype vs Reality," (November 8, 2009, accessed August 12, 2013) available from http://www.gamepilgrimage.com.

- 4. "sheath", "Sega Genesis vs Super Nintendo," (November 8, 2009, accessed August 12, 2013) available from http://www.gamepilgrimage.com, Super Nintendo Background Planes.

- 5. "sheath", "Sega Genesis vs Super Nintendo," (November 8, 2009, accessed August 12, 2013) available from http://www.gamepilgrimage.com, Sega Genesis Sprite Max & Sizes.

- 6. Semrad, "insert coin: The Power of Rumors...," Electronic Gaming Monthly, April 1991, 8.

Media

Print advertising, executive or developer interviews, editorials and opinion pieces that do not fit under Console History due to anachronisms will be reviewed here.

GameTrailers - GT

Review of GT's One-Shot - Prepare to Launch

Online video "documentaries" and comparisons are popular in the broadband accepted new millennium. Like most documentaries however, these videos tend to cherry pick facts and loosely adhere to their own arbitrary rules. Videos such as these tend to have only one consistent goal to garner website hits by any means necessary. In just such an attempt, Game Trailers (GT) posted a launch library comparison of most well known game console released in the United States.1 So GT's viewers could compare game console launches from the past to the up coming launch of the next generation Sony Playstation and Microsoft Xbox consoles, the narrator states "rather than limiting our list of games that hit day one with the hardware, we went with more generous launch windows. But in general, if you missed Christmas you missed launch." 2 The point of this article is to explore Game Trailer's launch lists and compare them with the game lists on Gamepilgrimage, which were compiled using various online databases and continue to be discussed at length in appropriate web forums.

Discrepancies with that general rule run throughout GT's launch comparison however. After covering a smattering of "Atari Age" (2nd Generation) Console launches, GT launched into the "post great fall" 8-bit (3rd Generation) consoles. The Nintendo Entertainment System (NES) launch is listed by GT in 1985, when that is actually just a test market with nowhere near mass market numbers for hardware or software published.3 So Game Trailers cheated the NES of its full 1986 national launch. GT may have decided to place the NES 1986 launch at some earlier month and excluded Fall releases arbitrarily. Either way, the 1985 NES library alone fails to represent what the average consumer saw on store shelves, if they saw them at all. By the time most US consumers saw the NES there should have been up to thirty four games on the shelves by Christmas of 1986. Sega's Master System was also released nationally in the US by Christmas of 1986. However, GT excluded Marksman Shooting / Trap Shooting and The Ninja (maybe 1987) from the Master System list. With those games included the Master System launch selection was twenty three titles including double carts. The NES being launched nationally in 1985 is a common misconception especially in the journalist community, and having a couple of games off the Master System list is reasonable given the wide variety of release dates available.

Game Trailer's research becomes fuzzier, though, with the 16-bit (4th generation) consoles. Missing from the US Genesis launch list are Forgotten Worlds, Golden Axe, Herzog Zwei, Revenge of Shinobi, and World Championship Soccer, yet GT includes Phantasy Star II (March 1990) and Tetris (Japan only release, very rare). The US Genesis launch list was eighteen titles with the above titles corrected. The TurboGrafx-16 launch was badly represented in GameTrailer's video however. Bonk's Adventure (maybe 1990), Dragon Spirit, Fantasy Zone, Neutopia, Ordyne (maybe 1990), Pac-Land (maybe 1990), Sidearms, Takin' It to the Hoop (maybe 1990), and Victory Run (maybe 1991?) are excluded from the TG16's 1989 library. In addition GT fails to mention the Turbo CD launch in the same year with Fighting Street, Monster Layer and Y's Books I&II. The total 1989 library for the TurboGrafx-16 and Turbo CD by most accounts is twenty six titles, a good deal more competition for Sega's Genesis lineup than GT showed. Perhaps Game Trailers limited the Turbo library arbitrarily to a summer launch, but did not do the same with the Genesis. The Super Nintendo launch is, by GT's count, lacking Chess Master, D-Force, Hole in One Golf, Home Alone, Joe & Mac, Lagoon, Super Baseball Simulator 1.000, Super Castlevania IV, and True Golf Classics: Waialae. RPM Racing (1992) is oddly included however. Including the missing 1991 titles makes the Super Nintendo launch 30 titles, very comparable to the original NES' national launch numbers. Perhaps GameTrailer's researchers arbitrarily excluded games released after September 1991 while introducing factual errors by leaving some in.

Moving on to the 32-bit (5th generation) consoles, GT unevenly limits the Saturn's launch titles to its Summer 1995 pre-launch and compares that to most of the PS1's 1995 library. This kind of library comparison is typical of journalistic websites. The fifth and sixth generation (32-bit through 64-bit, or 3D consoles) will be covered elsewhere to keep this a comparison of 2D console launch games. As always, please use the Contact page to submit any revisions to the Gamepilgrimage game lists, or view the relevant topic in WAG forums.

- 1. "GT One-Shot Video - Prepare to Launch | GameTrailers," (October 15, 2013, accessed October 23, 2013), available from http://www.gametrailers.com.

- 2. "GT One-Shot Video - Prepare to Launch | GameTrailers," (October 15, 2013, accessed October 23, 2013), available from http://www.gametrailers.com, (0:30-0:41).

- 3. "Aquamarine," "Nintendo Historical Shipment Data (1983 - Present)," October 21, 2013, accessed October 23, 2013), available from http://www.neogaf.com/forum/.

Gamepro

Street Fighter II Coverage 1992-1993

Starting with the release of Street Fighter II The World Warrior on SNES in late 1992, Gamepro magazine began a hype campaign, lauding the SNES' strengths in regard to the Genesis. The review gave Street Fighter II: The World Warrior a perfect score, which was not rare in Gamepro magazines. Notable deficiencies in the Arcade conversion, such as the lower resolution or that the digital voice samples cut out when two samples were to play at once, went without mention. The following 6 months of Gamepro issues were loaded with multi-page spreads of "tips and tricks" and "strategies." This continual promotion of the SNES game through Christmas '92 into the new year was unprecedented in US game magazines at the time, and is probably exemplary of how popular the Street Fighter II franchise had become.

Street Fighter II The World Warrior SNES Review (Page 1)

Street Fighter II The World Warrior SNES Review (Page 2)

March 1993 saw the first hint of the Street Fighter II franchise being released on other consoles. Gamepro dedicated a 1-page article to announcing both a Mega CD and PC-Engine HuCard version of Street Fighter II Champion Edition.

Street Fighter II CE Import Preview

This preview, besides mistyping the projected release date of the HuCard version of Street Fighter II: Champion Edition, sneers at SNES fans for thinking the game would never arrive on "other" platforms. It also discusses both the Mega CD and PC-Engine receiving a new 6-button control pad to coincide with the game. With no pictures to look at, this preview provided little substance for owners of these platforms.

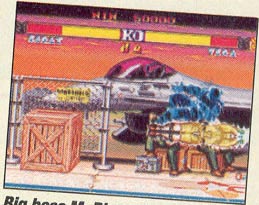

By June, however, Gamepro had a two page spread of the Genesis version of Street Fighter II: Champion Edition. This preview featured an 80% finished build of the game with huge black bars on the top of the screen for the energy bars to sit in. The implication at the time was that Genesis version had to cut the screen size down considerably in order to handle the game. Gamepro offered little analysis outside of an allusion to "gurgling" noises which might have been a snark against the Genesis sound chip, which would become Gamepro and EGM's mode of operation later the same year.

Street Fighter II CE Genesis Preview (Page 1)

Street Fighter II CE Genesis Preview (Page 2)

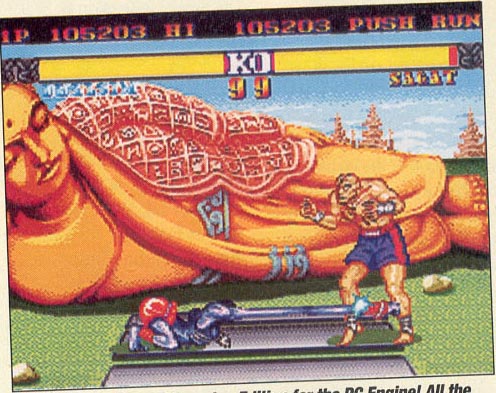

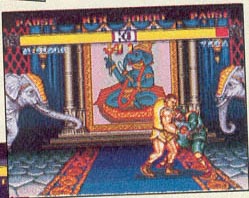

Gamepro's July 1993 issue featured a three page article of not only the Genesis and PC-Engine versions of Street Fighter II Champion Edition, but also of Street Fighter II Turbo for the SNES. The PC-Engine shots were some of the first shots printed in the US, and demonstrated a marked improvement over the Genesis shots from the previous issue. The Genesis shot (singular) still showed the huge black bar at the top of the screen. There was also no mention of any "Hyper Fighting" mode being added to the Genesis version.

SFII Multi Platform Preview Page 1 (SNES)

SFII Multi Platform Preview Page 2 (Genesis)

SFII Multi Platform Preview Page 3 (PC-Engine)

SNES:

Genesis:

PC-Engine:

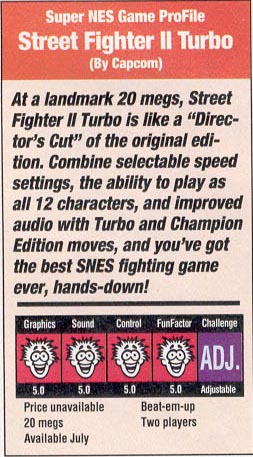

Street Fighter II Turbo's review for the SNES comprised one of Gamepro's major August 1993 headlines. This review promoted that the SNES game contains both Champion Edition and Turbo. Notably absent from this issue is any mention of the upcoming Genesis title soon to be redubbed "Special Champion Edition". Gamepro granted Street Fighter II Turbo, like it's predecessor on the SNES, a perfect rating in all categories following a 9 page review. Several months would pass before any mention of a Genesis equivalent to Street Fighter II was made by this magazine.

Street Fighter II Turbo (SNES) Review (Page 1)

Street Fighter II Turbo (SNES) Review (Page 2)

Street Fighter II Turbo (SNES) Review (Page 3)

Street Fighter II Turbo (SNES) Review (Page 4)

Street Fighter II Turbo (SNES) Review (Page 5)

Street Fighter II Turbo (SNES) Review (Page 6)

Street Fighter II Turbo (SNES) Review (Page 7)

Street Fighter II Turbo (SNES) Review (Page 8)

Street Fighter II Turbo (SNES) Review (Page 9)

Not even remotely all of the screenshots:

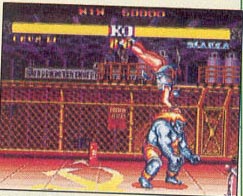

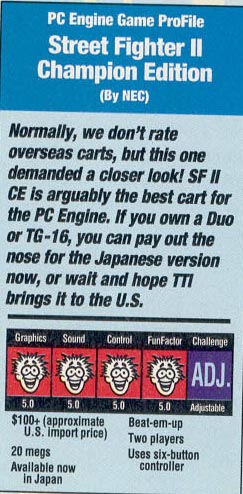

Gamepro did offer a two page article in September dedicated to Street Fighter II Champion Edition, but not for the Genesis. This issue published a review/preview of the finished PC-Engine HuCard that had been released in June in Japan.

Street Fighter II CE PC-Engine Review (Page 1)

Street Fighter II CE PC-Engine Review (Page 2)

The review of Champion Edition for PC-Engine featured significant detail. Mentioning flicker that only an "eagle's eye" could catch, as well as the "surprisingly clear" voice samples coming out of the otherwise "distorted" PC-Engine sound chip are the highlights of this review. The screenshots, though, show that the game was running at the same resolution as the original SNES game of the year before, rather than having to be cropped like the earlier Genesis preview shots were. Like Street Fighter II Turbo and Street Fighter II for the SNES, the PC-Engine game received a perfect score of all 5.0s.

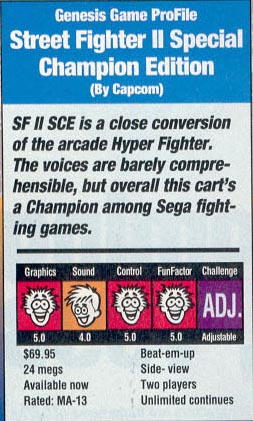

Finally, in their October 1993 issue, Gamepro published another preview of the Genesis game, now redubbed "Special" Champion Edition. The Genesis game was revealed to be Street Fighter II Turbo with a "Champion" mode like the previously reviewed SNES game. Gamepro also described Special Champion Edition as just "as good as the others for the SNES." The Genesis game, according to Gamepro, features "improved" graphics and "large, fully detailed sprites, great color shading, and better vivid visuals to the backgrounds. Notably lacking from the screenshots were the then legendary black bars on the top of the screen.

Street Fighter II SCE Preview

The promise of a full review in the November issue was delivered upon, and then some. Gamepro treated the Genesis release of Street Fighter II Special Champion Edition a three page spread in order to demonstrate the additional combos and moves over the original SNES game of the year before. Yet Gamepro went out of their way to malign the audio, describing it as though a "string-and-cups kiddy phone" underwater would sound better than the Genesis game's audio. They also state: "Without a question, doubt, or hesitation, the Super NES version beats out the Genesis edition by virtue of better graphics and sounds." This, when combined with an exaggerated comparison of the Genesis and SNES' hardware color limitations which makes the SNES appear to be four times more colorful in the average game, along with a description of the audio as being "garbled", left the Genesis version looking like a second rate substitute for the SNES "original".

Street Fighter II SCE Review (Page 1)

Street Fighter II SCE Review (Page 2)

Street Fighter II SCE Review (Page 3)

The SNES release of SFII Turbo does not have four times the colors on screen as the Genesis version, it has a little over twice the colors which are primarily taken up in the backgrounds. The character sprites are identical between all three versions.

Moreover, the Genesis game is doing something that Gamepro missed, and that sets it apart from almost all other Genesis games and the PC-Engine version. Digital instruments and voice samples play at the same time. Out of an analog sound chip with only one digital channel, this should not be disregarded. Conversely, the PC-Engine version has very clear voice samples, but literally every sound effect and musical instrument is PSG synthesized instruments. Had Capcom chosen to use FM or PSG instruments instead of digital audio samples for the sound effects and music in the Genesis the voice samples would likely have been much higher quality. This is only one disparity between the presentation that Gamepro made of these three games, and the presentation that the games make of themselves.

These PC-Engine, SNES and Genesis games are so similar in audio and video that they can easily be mistaken for one another by consumers. As such, this page is designed to demonstrate the similarities of each version. Each section is separated only by the screenshots from Gamepro magazine, and yet no version stands out in color or on screen detail.

Something that was even more confusing back in '93 was the order in which these games were reviewed, and the amount of coverage each received. From August until November of 1993, all the US had according to Gamepro was the Super NES version of SFII Turbo. When the Genesis game was finally reviewed, after the ~$100 import of the PC-Engine version, it was maligned and clearly placed a distant second to the SNES game in the States. In other words, provided both Special Champion Edition and Turbo were not on the shelves at the same time, Gamepro's readers only had a choice between the excellent high quality screenshots of Turbo to look at, and low quality "80% build" shots of an up and coming Champion Edition for the Genesis. In time without the Internet, three months was a long time to wait to find out that a comparable game was available on both systems.

Gamepro scoreboards simply imply that two versions of Street Fighter II from 1993 are perfect, and one is flawed. Let the reader view the video comparison posted under 16-bit Arcade Comparisons to see if such a comparison holds up.

Also view the games fact sheets for screenshots and release information. Below are the maximum color counts of the emulation screenshots shown on each game's page.

Game (System): Maximum Simultaneous Colors of Screenshots shown

Street Fighter II Champion Edition (PC-Engine): 87

Street Fighter II Special Championship Edition (Genesis): 53

Street Fighter II Turbo (SNES): 135

Retro Gamer

Issue 77

Review of Damien McFerran's "Retroinspection: Sega 32X"

Introducing his editorial on the 32-bit add-on for the Sega Genesis, Damien McFerran, co-maintainer of the Mean Machines Archive1 and Nintendo Life2, offers his very subjective opinion. "How do you take half a decade's worth of critical and commercial success and flush it down the toilet," McFerran posits, "Easy: you release a device like the Sega 32X." 3 Asserting that Sega was "at the height of its powers" by 1990, but "took far too many risks" with hardware by 1995, McFerran fails to cite which industry experts claim that the "commercially disappointing" Mega CD was a prelude to the "disastrous retail performance" of the 32X.4 McFerran similarly offers a crude history of the 32X and Saturn at retail before introducing Scot Bayless, Senior Producer at Sega of America from 1990-1994.5 The subsequent several pages are exemplary of the hostility towards Sega hardware that has accumulated over the last fifteen years. The comments of Scot Bayless and Marty Franz published in these pages challenge and disprove a number of common fallacies surrounding the 32X, and even some for the Saturn's development. McFerran, however, only posits hyperbolic questions and maintains an extremely negative tone throughout his six page editorial.

Bayless recalls the 32X development origins at Winter CES 1994 in Las Vegas. Joe Miller, Head of Sega of America Research and Development, called Bayless and a couple of others into a teleconference with Hayao Nakayama. The call resulted in a move away from an enhanced Megadrive, apparently being worked on by Sega of Japan's Hideki Sato, toward a response to Atari's Jaguar. To which Joe Miller, according to Bayless, pushed for letting Sega of America develop a solution. Nakayama agreed, and the 32X was conceived on a hotel notepad when Marty Franz sketched two Hitachi SH-2 processors with individual frame buffers. Bayless continued by explaining that Sato's "Jupiter" was squeezed out due to cost factors by the 32X. McFerran then interjects his first positive statement: "From an engineering standpoint, the machine certainly had a lot of potential." 6 Bayless opines that the 32X's graphics subsystem was "brilliantly simple: something of a coder's dream" with "twice the depth per pixel of anything else out there." 7 The way the 32X handles 3D, Bayless supposes, was not being attempted "outside the workstation market." 8 In spite of all of this, McFerran bookends the first and second pages with an enlarged self-quote of the 32X being "the straw that broke the camel's back" and one of Bayless more baseless assertions that 32X's mere existence made Sega "look greedy and dumb to consumers." 9

McFerran describes "much brow-forrowing" at Sega of Japan due to the Megadrive's third place status in Japan and their "consensus" that all available resources should have been focused on Saturn.10 Apparently in direct conflict with this consensus was Nakayama himself, who took notice of the Genesis' "incredible commercial performance" and Sega of America's subsequent insistence of its continued marketability. Bayless recalls "there was a consensus at Sega of America that making an add-on for the Megadrive was the right move." 11 Nakayama's ensuing call to get the 32X out by the end of 1994 was due, Bayless suspects, to his doubt on whether "the Saturn would make it to market within 1994." 12

Suppositions about how, or whether, the 32X and Saturn would coexist seemed to abound at Sega of America at least. Despite McFerran's assertion of a consensus against the 32X in the parent company, Bayless remembers "the guys at Sega of Japan were great - especially Sato's team." 13 Any perceived tension between Sega's branches at the time are attributed to the "super double-secret-crunch-mode" and frayed nerves over delays such as the two week pause when the 32X development kit had one of its SH-2s fail. "The guys in Japan were awesome," Bayless persists, "they worked their tales off to help us." 14 The only problem Bayless notes was the difficulty in translating English hybrid "technical Japanese" documentation, which was being sent to Sega of America as it was being written.

McFerran, here, fails to notice that Bayless' account shows Sega of Japan was engineering the 32X based on Sega of America's work. The writer does note that the 32X and Saturn shared the same CPUs but used them very differently. Oddly, Bayless describes the Saturn's usage of quadrilaterals as "essentially a 2D system with the ability to move four corners of a sprite ... [to] simulate 3D space." 15 Continuing that the Saturn's hardware rendering was bottlenecked by a "very high" pixel overwrite rate and "memory access stalls," Bayless shows preference for his team's design.16 These supposed problems with the Saturn being as much dependent on the quality of the code as the 32X's ability to display 3D at all seems to escape Bayless' notice.

The 32X doing "everything in software" but having "two fast RISC chips tied to great big frame buffers and complete control to the programmer" causes Bayless to lament that the Saturn had not adopted a similar approach. Bayless' next statement should not be missed, "that ship had already sailed long before the green light call from Nakayama." Depending on how long before January 1994 the Saturn's hardware was solidified, Bayless' recollection stands against the popular theory of any redesign of the Saturn after the first Playstation's specifications were announced in mid 1993.

McFerran then calls for a consideration of "the state of the market at the start of 1994." 17 The editor claims the 3DO and Jaguar caused "nervous glances ... from Sega and Nintendo" before asserting "16-bit games were beginning to look look terribly outdated." 18 The only observation McFerran offers on the actual state of the market in 1994 is that "something was certainly needed to keep the momentum going." 19 In reality the US game industry, which Sega as a company had become dependent on, had entered "a three-year slump in 1993" with Nintendo reporting twenty-four and thirty-two percent drops in profits the next two years respectively.20 According to Financial World's Kathleen Morrison though, Nintendo actually lost forty percent of its profits from 1992 to 1993 whereas Sega's earnings dropped sixty-four percent the same year.21 Citing NPD group data, along with some of the same articles above, journalist Steven Kent observes in his book The Ultimate History of Video Games that the US console market dropped by thirty-six percent in total revenue from 1993 to 1995. 22

The Wall Street Journal's Jeffrey Trachtenberg observed in September of 1994 that Nintendo and Sega were preparing massive marketing budgets to battle for revenue that holiday season. The article features Sega's William White and Nintendo's Peter Main extolling their respective marketing and advertising plans before citing Michael Wallace, an analyst with UBS Securities. Wallace reported that the world wide industry was expected to "slip to $2.8 billion this year from $3 billion in 1993." 23 Wallace was also directly quoted as saying: "The market is saturated, because almost everyone who wants a video game has one," to which Trachtenberg summarized that Wallace considered 35 million "16-bit players" saturation for the US market. In response the article cited William White again, who stated that Sega expected the 32X to be on the market for three to five years and sell one million units by April 1995.24

Neither McFerran or Bayless make any observations about the 32X's role in correcting the fact that Sega's revenue had declined much more sharply than Nintendo's had at the beginning of the second full year of market decline. McFerran also placed a list of "specifications" for the 32X in a sub column, which he ends by stating flatly "it would be easier to list the reasons why the system was a failure, but there are some positive things to mention." 25 The editor then reluctantly admits to the 32X launch receiving three well adapted arcade conversions, and the add-on's affordability, before tossing out that "it's just a shame that it sold so poorly because the potential was there for greatness." 26

Turning the page, Bayless notes that Sega of America was making Saturn games even while "the 32X had to ramp up ... to hit its timing." 27 Apparently the two system's sharing SH-2's resulted in the 32X facing shortages in the face of the "decoupled" Saturn. McFerran chimes in that Bayless' team was "essentially attempting the impossible," citing only the ten month development goal and resource management as evidence. Also, according to McFerran, the Saturn's November 1994 launch in Japan was "a bombshell that essentially wrecked the 32X's chances of any kind of success." After reflecting on the fact that Saturn and 32X were releasing much more closely than was assumed, Bayless recalls consumers started to ask "why should I buy a 32X when the Saturn is only a few Months away?" 28 Yet the U.S. launch date of the Saturn was unknown by anybody, least of all consumers up to and following its surprise launch in May of 1995. So, the only framework for such a theoretical consumer question is that they might have preferred to wait ten to twelve months for the Saturn, which 1995 sales of the PS1 and Saturn significantly discredits.

If consumers were thinking about the far off Saturn in 1994 it is not evidenced in the 32X's sales figures. McFerran also calls the early Saturn launch in Japan the thing that transformed "the 32X from a life-saving blood transfusion ... into a poisonous tumour that would further erode the company's standing in the global marketplace." 29 Begrudgingly admitting that "the 32X experienced a reasonably successful launch in the West" while calling the $159 launch price a "hefty price tag," McFerran reports that "the machine shifted its initial shipment of 600,000 units with ease; it was even reported at the time that demand had far outstripped supply." 30 Even while admitting that the same successful launch occurred in Europe McFerran only credits that to Sega's "power" in that region.

Bayless also observes that the marketing stance of the 32X being "a bridge from Mega Drive to Saturn ... made us look greedy and dumb to consumers, something that a year earlier I couldn't have imagined people thinking about us. We were the cool kids." 31 Some further research needs to be done on how Sega's reputation as "the cool kids" was attained and how much that reputation had to do with the perception of cutting edge hardware. In a sub-column roughly one-third of the page is a direct print interview between Retro Gamer and Marty Franz, Vice President of technology for Sega of America from 1993-1997. Franz describes the initial call from Nakayama as "more like a summons" for Joe Miller and Steve Payne to hear Nakayama's vision in Japan. Franz recalls that "within a few weeks a small group of us [were] on a plane to Japan to discuss the product." Franz concurs with Bayless that the 16-bit market was going to earn Sega more income than the Saturn would in the near future. Adding much needed detail to the early hotel room 32X hardware sketch, Franz asserts "we really liked the Hitachi SH-2 CPUs that the Saturn had and felt they were the star of the show." 32

Much the same as Bayless' recollection of the early Saturn architecture, Franz thus corroborates that the dual SH-2s within the Saturn were already well known by the beginning of 1994. Franz also disavows any known friction between Sega of America and Sega of Japan at the time. Describing the 32X as "a fast paced development process with a great product produced at the end," Franz and Bayless agree that the two divisions of Sega worked as a team despite "a great deal of distance between us." 33

Only the dual SH-2s were in common between the 32X and the Saturn. The focus, according to Franz, was on the development timeline while pushing "everything we could imagine that would enable great games." 34 Franz concludes that the team knew that CD-ROM based next generation consoles were eventually going to take over, but thinks that any perceived deficiencies in the 32X's library were due to the system's short development cycle and lack of third generation software.

McFerran continues on the next page by claiming that the 32X failed due to "a distinct lack of compelling software." The editor then cites Bayless, who supposes that demand fell because "the launch mix for the 32X was horrible ... some of the games were pretty good, but in context they needed to be amazing." 35 Bayless persists that the Playstation launch in Japan made "any argument in favor of the 32X ... ridiculous." While McFerran remains fixated on proving a design flaw, Bayless insists "the games in the queue were effectively jammed into a box as fast as possible ... those games were deliberately conservative, they did nothing to show off what the hardware was capable of." 36 Clearly missing the point, McFerran responds by asking whether he ever believed in the 32X, to which Bayless replies "32X was a great hypothesis ... but in execution it was disastrous." 37 The rest of Bayless analysis had to do with "hardware ... industrial design and games" being "late or buggy - or both." 38 "I spent weeks working with id Software's John Carmack," Bayless continues "who literally camped out at the Sega of America building in Redood City trying to get Doom ported ... and he still had to cut a third of the levels." 39 Whether the time frame caused the 32X version of Doom to be limited to 3 Megabytes, compared to the 4 Megabyte source material, is not addressed.

The rest of the article is prefaced with another sub-panel with the Genesis Sega CD combo unit, the CDX, titled "Firing Blanks" and the Megadrive, Mega CD and 32X dubbed "Three's a crowd." 40 Bayless continues his previous thoughts by claiming that Sega should have dropped the 32X in the Spring of 1994. By 1995, Bayless recalls, "everybody knew ... admitting it publicly that the 32X was a mistake wasn't an option." 41 From there things just get ugly. Bayless asserts, and McFerran makes sure to emphasize in huge quotes, "We stormed the hill and when we got to the top we realized it was the wrong damn hill." 42 Claiming that working for Sega from 1992 through 1994 was "like watching the Hindenburg in slow motion." Bayless goes on to list the Mega CD's "cheap consumer drives" and emphasis on Full Motion Video, "positioning the 32X as an orphan system," claiming the Saturn was just a 2D system again, and then trashing peripherals like the Activator and "Sega VR." In response to which, Bayless feels consumers "voted with their wallets and stayed away." 43

Bayless concludes by correctly explaining that the success of an organization is very much contingent on the transparency in communication in each individual group. Whether Microsoft exemplifies this motif, as Bayless claims, is certainly debatable, but clear communication within an organization is tantamount to success. Especially in light of the interviews conducted by Retro Gamer here, the 32X itself was clearly not a cause of Sega's ultimate downfall as a hardware manufacturer in 2001. McFerran observes Bayless' opinion of the 32X being a "warning" to present hardware manufacturers, but the cause of why it failed has yet to be thoroughly and objectively explored, least of all by journalists.

- 1. "The Mean Machine's Archive -90's Gaming Magazine," (accessed September 16, 2010) available from http://www.meanmachinesmag.co.uk/ (archive.org August 22, 2008).

- 2. "Nintendo Life," (accessed September 16, 2010) available from http://www.nintendolife.com/ (archive.org August 22, 2008).

- 3. McFerran, Damien. "Retroinspection: Sega 32x." no. 77: 45.

- 4. McFerran, Damien. "Retroinspection: Sega 32x." no. 77: 45.

- 5. McFerran, Damien. "Retroinspection: Sega 32x." no. 77: 45-49.

- 6. McFerran, Damien. "Retroinspection: Sega 32x." no. 77: 45.

- 7. McFerran, Damien. "Retroinspection: Sega 32x." no. 77: 45.

- 8. McFerran, Damien. "Retroinspection: Sega 32x." no. 77: 45.

- 9. McFerran, Damien. "Retroinspection: Sega 32x." no. 77: 45-46.

- 10. McFerran, Damien. "Retroinspection: Sega 32x." no. 77: 46.

- 11. McFerran, Damien. "Retroinspection: Sega 32x." no. 77: 46.

- 12. McFerran, Damien. "Retroinspection: Sega 32x." no. 77: 46.

- 13. McFerran, Damien. "Retroinspection: Sega 32x." no. 77: 46.

- 14. McFerran, Damien. "Retroinspection: Sega 32x." no. 77: 46.

- 15. McFerran, Damien. "Retroinspection: Sega 32x." no. 77: 46.

- 16. McFerran, Damien. "Retroinspection: Sega 32x." no. 77: 46.

- 17. McFerran, Damien. "Retroinspection: Sega 32x." no. 77: 46.

- 18. McFerran, Damien. "Retroinspection: Sega 32x." no. 77: 46.

- 19. McFerran, Damien. "Retroinspection: Sega 32x." no. 77: 46.

- 20. "Nintendo Expects." Television Digest 1994, 13.

- 21. Morris, Kathleen. "Nightmare in the Fun House. (Cover Story)." Financial World 164, no. 5 (1995): 32.

- 22. Kent, Steven L. The Ultimate History of Video Games. New York: Three Rivers Press, 2001, 500.

- 23. Trachtenberg, Jeffrey A. "Advertising: Sega and Nintendo Prepare to Do Battle over Holiday Season Sales." Wall Street Journal - Eastern Edition (1994).

- 24. Trachtenberg, Jeffrey A. "Advertising: Sega and Nintendo Prepare to Do Battle over Holiday Season Sales." Wall Street Journal - Eastern Edition (1994).

- 25. McFerran, Damien. "Retroinspection: Sega 32x." no. 77: 46.

- 26. McFerran, Damien. "Retroinspection: Sega 32x." no. 77: 46.

- 27. McFerran, Damien. "Retroinspection: Sega 32x." no. 77: 47.

- 28. McFerran, Damien. "Retroinspection: Sega 32x." no. 77: 47.

- 29. McFerran, Damien. "Retroinspection: Sega 32x." no. 77: 47.

- 30. McFerran, Damien. "Retroinspection: Sega 32x." no. 77: 47.

- 31. McFerran, Damien. "Retroinspection: Sega 32x." no. 77: 47.

- 32. McFerran, Damien. "Retroinspection: Sega 32x." no. 77: 47.

- 33. McFerran, Damien. "Retroinspection: Sega 32x." no. 77: 47.

- 34. McFerran, Damien. "Retroinspection: Sega 32x." no. 77: 47.

- 35. McFerran, Damien. "Retroinspection: Sega 32x." no. 77: 48.

- 36. McFerran, Damien. "Retroinspection: Sega 32x." no. 77: 48.

- 37. McFerran, Damien. "Retroinspection: Sega 32x." no. 77: 48.

- 38. McFerran, Damien. "Retroinspection: Sega 32x." no. 77: 48.

- 39. McFerran, Damien. "Retroinspection: Sega 32x." no. 77: 48.

- 40. McFerran, Damien. "Retroinspection: Sega 32x." no. 77: 49.

- 41. McFerran, Damien. "Retroinspection: Sega 32x." no. 77: 49.

- 42. McFerran, Damien. "Retroinspection: Sega 32x." no. 77: 49.

- 43. McFerran, Damien. "Retroinspection: Sega 32x." no. 77: 49.

Sega Saturn.CO.UK

Review of "Aydan's" Interview with Ezra Dreisbach

Several years ago, Sega Saturn Co. UK interviewed Ezra Dreisbach of Death Tank and Lobotomy fame. 1 When compared with one of Dreisbach's previous interviews2 and comments from other developers such as Pitbull's Steve Palmer,3 this interview has many points worth discussing.

When the average reader, or editorialist, sees excessively negative comments like Dreisbach's here they tend to jump to a conclusion. Another thing these statements actually point to is high level versus low level programming. In this case, that means games that were programmed to the hardware using Assembly language versus games that were coded using high level C language programming kits.

Comments like Dreisbach's persist in regard to the Saturn and Playstation 1 despite the relative performance of software on both systems. One developer can be found saying the Saturn was a challenge, but that developer expected their game code to easily port. They expected the Saturn to run exactly like a PC or PS1. Some expected to not have to learn much about the hardware. The programmer who looked at the hardware and then designed a game proved the Saturn was competitive at 3D even if it was difficult.

Based on his previous interview Dreisbach just didn't like quadrilaterals (quads), apparently triangles are *way* better than squares. Based on the latest interview, Dreisbach also thought the Saturn design for 3D games was "stupid". Yet looking solely at the production software, Dreisbach's comments seem to have more to do with the portability of code between the Saturn and other systems than they do with the system's limits at 3D rendering. Thanks to games Dreisbach coded himself, the Saturn's 3D capabilities were displayed at the same level or higher as contemporaneous machines.

Some questions remain on this topic even after all these years. Dreisbach makes comments in both interviews about the Saturn not being able to "stretch" its quads to create a long wall with only a few polygons. Apparently a flat sided object can effectively be stretched indefinitely on the PS1 and the Saturn needs to build it out of quads. This needs to be confirmed and explained. Also, the Saturn's quads needed to have one end pinched into another to make a triangle. It is still unclear whether or not a "pinched quad" on the Saturn was more or less hardware intensive. The texture art needed to be modified from a triangle based engine to a quad based engine however.

Perhaps the most significant of Dreisbach's comments are on how coding specifically to the Saturn affected porting software to other systems. The difficulty Dreisbach describes in porting Saturn code to the Playstation, when combined with comparing the production level software 4, creates many questions about how many other talented programmers worked on Saturn games. If most of the Saturn's games were made were ground up designed, would the Saturn still be just as poorly designed in our estimation?