1991: Hype vs Reality

Not until March 1991 did issues of Gamepro and Game Players dedicate an editorial to the Super Nintendo. Unlike EGM's numerous articles comparing specifications provided by marketing departments, both Gamepro and Game Player's focused on the games that had already been released in Japan. Gamepro exhibited pictures of Super Mario World, F-Zero and Final Fight, while pointing squarely at the "massive support by third-party licensees" as the system's biggest advantage.1 Game Player's Tom Halfhill argued similarly that launch games for the Super Famicom, which was the console's final name in Japan, could have been made as well on the Genesis and TG16. Crassly dismissing exaggerated maximum color count and resolution differences for each system, Halfhill concluded "quality software and clever marketing are more likely to carry the day." 2 Marketing influenced more than the sales of these consoles or their games, it created the popular perception about the machines' capabilities and the quality of their libraries.

Not until March 1991 did issues of Gamepro and Game Players dedicate an editorial to the Super Nintendo. Unlike EGM's numerous articles comparing specifications provided by marketing departments, both Gamepro and Game Player's focused on the games that had already been released in Japan. Gamepro exhibited pictures of Super Mario World, F-Zero and Final Fight, while pointing squarely at the "massive support by third-party licensees" as the system's biggest advantage.1 Game Player's Tom Halfhill argued similarly that launch games for the Super Famicom, which was the console's final name in Japan, could have been made as well on the Genesis and TG16. Crassly dismissing exaggerated maximum color count and resolution differences for each system, Halfhill concluded "quality software and clever marketing are more likely to carry the day." 2 Marketing influenced more than the sales of these consoles or their games, it created the popular perception about the machines' capabilities and the quality of their libraries.

All game magazines that mentioned the Super Nintendo prior to its US launch noted something about its games displaying more colors on screen, but they disagreed on how significant the gap was. This disparity in journalist reviews was probably most influenced by the outputs and target of each of these system's graphics. TurboGrafx, Genesis and SNES consoles were packaged with RF cables intended for the coaxial cable input of an NTSC television, which was the standard in the US and Japan. Answering one Phil Kennington in the February 1991 issue, EGM ranked all available output cables for game consoles from RF, to Composite, and finally RGB. The editor also explained that EGM had to modify the hardware of all of their game consoles to support RGB monitors.

All game magazines that mentioned the Super Nintendo prior to its US launch noted something about its games displaying more colors on screen, but they disagreed on how significant the gap was. This disparity in journalist reviews was probably most influenced by the outputs and target of each of these system's graphics. TurboGrafx, Genesis and SNES consoles were packaged with RF cables intended for the coaxial cable input of an NTSC television, which was the standard in the US and Japan. Answering one Phil Kennington in the February 1991 issue, EGM ranked all available output cables for game consoles from RF, to Composite, and finally RGB. The editor also explained that EGM had to modify the hardware of all of their game consoles to support RGB monitors.

A consumer who wanted to view their console of choice with anything better than RF cables in 1991 had to buy a brand new television if they wanted to connect with AV Composite cables (Yellow video, with Red and White audio cables). Composite cables required an investment of twenty dollars in addition to a new television that would also improve cable and VCR quality. Obtaining a cable compatible with an RGB monitor required an investment of around one hundred dollars and a specialized monitor that cost significantly more than the new televisions being sold in electronics stores.3 EGM admitted that game companies targeted the lower quality outputs that the mass market could buy in stores, which severely impacted how many distinct colors could appear on the consumer's screens.4 Answering similar questions, Gamepro warned one Spanky Smith of Greensville South Carolina that Japanese RGB cables could have been incompatible with US equipment.5

Unencumbered by pertinent facts, EGM proceeded to advocate the "Super Famicom." Showing computer generated shots of three dimensional trees in a preview for Hole In One Golf, immediately following a four page promotion for Super Mario World, EGM explained "The Super Fami, with its large color palate(sic), can show shadings that give the illusion of 3-D." When Hal's Hole In One Golf was actually published that Fall it was notably absent of any three dimensional objects as shown in EGM's preview.6 Hole In One Golf actually does exhibit a unique feature of the Super Nintendo in the same manner of other launch titles. The SNES's Mode 7 allowed Hole in One Golf a fly by of a very low color two dimensional still image of the courses. Hole in One's courses were strictly overhead and two dimensional, with a special angled view that rendered the landscape in low detail to show elevation.7

During any generation of hardware, effects that the systems handled with the least programming effort are employed in games more often and more uniformly than effects that developers had to hand code. Mode 7 was marketed by Nintendo, and their allies, to become synonymous with real time scaling and rotation. Scaling is the term used for simulated zooming of backgrounds or characters, rotation allows the same to turn like a wheel. Mode 7 could only scale and rotate a single two dimensional background layer, no SNES game scales characters or objects in a Mode 7 scene. The effect was most often used to "jazz up" certain non-gaming scenes and racing games. Mode 7 offered nothing that was not technically already being done in similar scenes on other consoles, and was totally trumped by arcade machines from the late 1980s. The effect had a distinctive look, however, and its frequent use was the most obvious characteristic of Super Nintendo games. These facts gave Nintendo the ability to easily point out the look and sound of Super Nintendo games and made rumors about the system's technical superiority seem true.

Introducing his April issue of EGM, Ed Semrad explained the importance of rumors to his readers and explained game magazines' function as free advertising for game companies. Semrad was also one of the first editors to print the term "vaporware" in regard to the Nintendo-Sony CD-ROM add-on for the affectionately abbreviated "Super Fami." 8 Even while Semrad lamented that "a very short nondescript press statement" tore the industry's attention from real consoles and games, the editor failed to note how similar that was to EGM's constant coverage of the SNES for the previous two years. In the previous issue's letter section, one T. Jones wrote that four different Nintendo representatives denied the accuracy of EGM's Super Famicom coverage so vehemently that their words were not fit for print. EGM responded that everything it had written about the SNES was correct regardless of the facts that the system name, its specifications and even the appearance of its games were significantly different in the final product.9

Introducing his April issue of EGM, Ed Semrad explained the importance of rumors to his readers and explained game magazines' function as free advertising for game companies. Semrad was also one of the first editors to print the term "vaporware" in regard to the Nintendo-Sony CD-ROM add-on for the affectionately abbreviated "Super Fami." 8 Even while Semrad lamented that "a very short nondescript press statement" tore the industry's attention from real consoles and games, the editor failed to note how similar that was to EGM's constant coverage of the SNES for the previous two years. In the previous issue's letter section, one T. Jones wrote that four different Nintendo representatives denied the accuracy of EGM's Super Famicom coverage so vehemently that their words were not fit for print. EGM responded that everything it had written about the SNES was correct regardless of the facts that the system name, its specifications and even the appearance of its games were significantly different in the final product.9

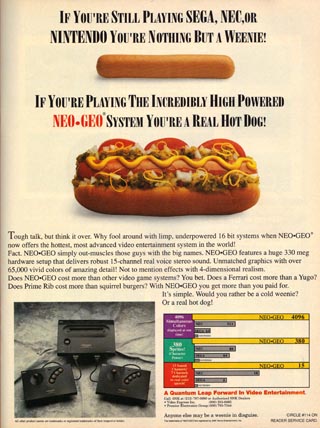

Hardware specifications in the game industry are only the product of marketing. It is evident from the published comments in all game related media that even the companies themselves were unsure of the technical limitations of their hardware. Advertising for the "consolized" NEO GEO arcade machine demonstrated the disparity between engineers and marketers very well. While SNK tried to convey that its arcade-machine-turned-console had "more" of everything, the TurboGrafx and Genesis specifications are reversed in two out of three categories.

Nintendo's public relations people out of Japan used similar terms to successfully, if inadvertently, convince EGM's publisher and editor to advertise the Super NES for several years in advance of its launch. As much as one million of the game industry's core demographic were exposed to EGM's Super Nintendo promotions every month. 10 By tossing out theoretical specifications without regard for television output, and knowing its audience did not have adequate programming knowledge of any system, Nintendo succeeded in establishing its upcoming console as "better" than anything else.

As a result of the Super Nintendo's preconceived superiority, the gaming media, retailers and public took an entirely different approach to Nintendo's second console than they did for the 16-bit consoles released two years prior. Instead of the usual skeptical "wait and see" consumer approach, the SNES might as well have already been a smashing success in all respects. The Genesis and TurboGrafx saw a couple of months of coverage prior to their US launch, which merely showed off the difference between their graphics and those of 8-bit consoles. The Super Nintendo, thanks largely to EGM, had seen monthly exposure for two years prior to its launch and enjoyed a full fledged buyer's guide in the August issues of Gamepro and EGM. Similar guides, that contained reviews, previews and pictures for every game announced for the US were finally published for the two existing 16-bit consoles the same year, which was two years after their US launch. Unfortunately for Nintendo, the hype failed to carry the NES' dominance into the new generation.

- 1. "The Unknown Gamer," "The Cutting Edge: Super Famicom Software," Gamepro, March 1991, 14.

- 2. Halfhill, "The Editor's View," Game Player's, March 1991, 4.

- 3. "Interface: Letters To The Editor, RGB For Genesis!..," Electronic Gaming Monthly, March 1991, 10.

- 4. "Interface: Letters To The Editor, SFX, too good for TV??..," Electronic Gaming Monthly, February 1991, 10.

- 5. "The Mail, Making the Connection," Gamepro, December 1991, 14.

- 6. "The Super Famicom Times: Hole In One Golf," Electronic Gaming Monthly, February 1991, 86.

- 7. "Fanatic Fan," "Overseas ProSpects," Gamepro, July 1991, 14.

- 8. Semrad, "insert coin: The Power of Rumors...," Electronic Gaming Monthly, April 1991, 8.

- 9. "Interface: Letters To The Editor, No SFX in US.," Electronic Gaming Monthly, March 1991, 10-11.

- 10. Semrad, "insert coin, 1,000,000 Readers!," Electronic Gaming Monthly, June 1991, 8.